Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Re-thinking Assessment: Counting with Mason

| Re-thinking Assessment: Counting with Mason Anne Dalke August 2007 |

In the several decades that I have been teaching college-level English (and related subjects) I have progessively de-emphasized grading. All of my current course pages have disclaimers like this:

"It is the instructors' feeling that concerns about grading are, for both teachers and students, a hindrance to the kind of open and productive interactions on which effective education depends. Moreover, no measure on a single scale can adequately represent any given student's distinctive engagement with and achievement in any given course....."

At the same time, of course, I have needed to assess my students' work, and have found a variety of ways of doing so, including public "performative assessments" that take place in the final class sessions, and self-evaluations that students hand in with their final portfolios of revised work. I've also tried to write about matters of assessment when I've published essays on alternative ways of teaching (see especially the final section of "Emergent Pedagogy").

Last week, while reading to my four-year-old great-nephew, I had an experience which got me thinking again about assessment: why we might need to do it, and how. I want to tell that story here.

One beautiful August evening, at his grandparents' farm in rural Maine, I offered to read to Mason. We gathered a stack of books, and went out onto the deck overlooking the pond. I tried to take him into my lap, but Mason insisted, instead, on pulling a rocking chair of his own alongside mine. He got into it and started rocking rapidly--my first indication that there were an internal gyroscope operating here, that was not going to be in synch with mine!

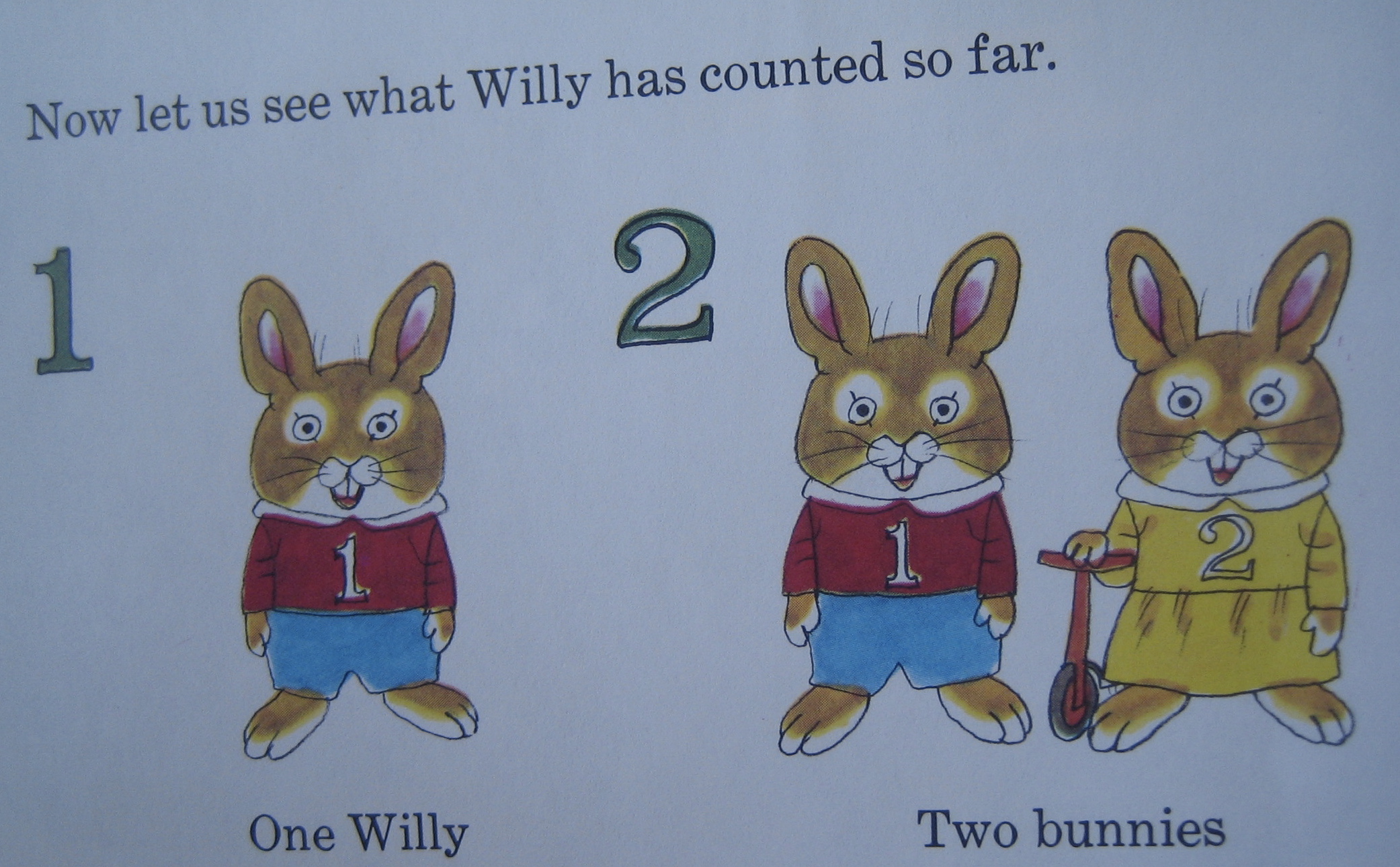

The book we chose to start was Richard Scarry's Best Counting Book Ever. It's a large book, brightly colored, jovial and jokey in its images, and quite serious in its intent. The front and end pages (which are identical) sum up the aim of the text, and its intent to encourage further learning: "Willy Bunny has learned to count. After you read this book, you be be able to count, too. Then see if you can add numbers the way Willy has added them below for his parents."

At this point in his life, numbers mean little to Mason. He doesn't know that he is four, can't show you four fingers in response to the number, will say "twenty, 'leven, nineteen" if you ask him to count something. So reading this very serious teaching book with him was a hoot. I'd be reading something on the top left-hand corner, while he'd be pointing out something in the bottom right-hand one. I'd be intoning, "One bunny and one bunny makes two bunnies. Both bunnies have two eyes, two hands, two feet, and two long ears..." while Mason ignored me, completely fascinated that there were "bugs in the trucks!"

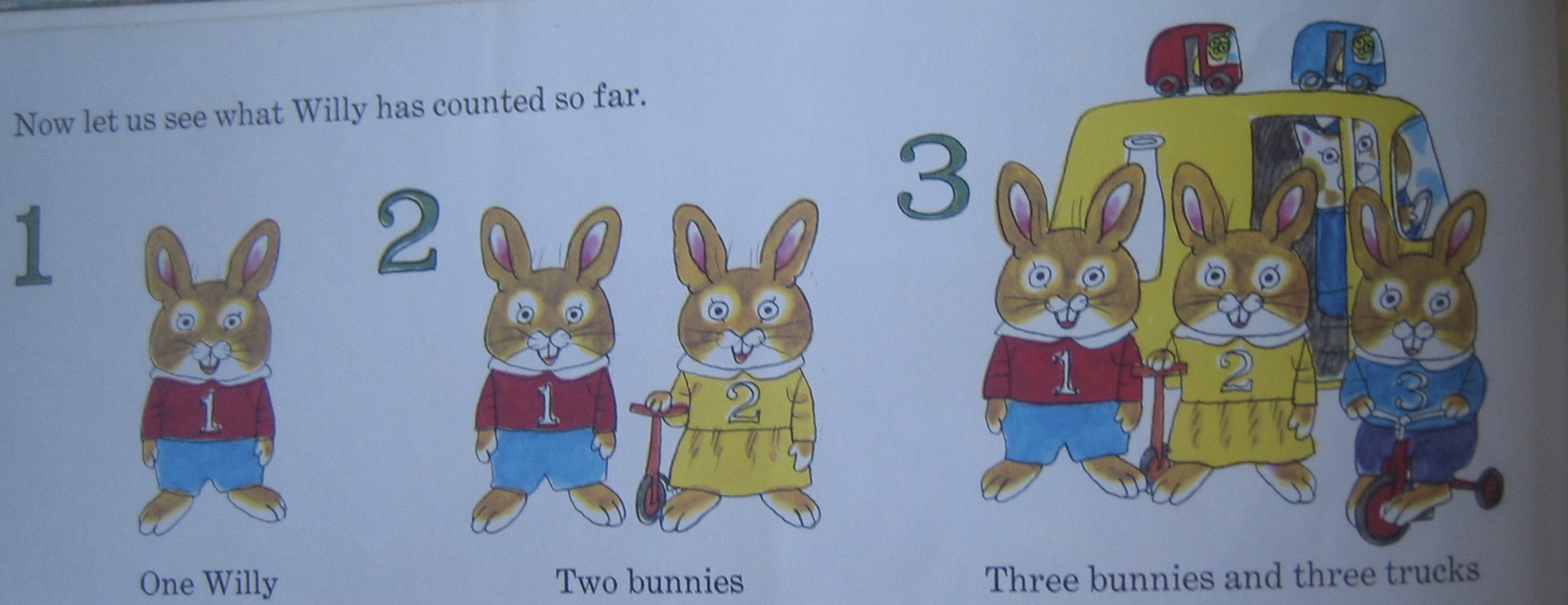

What I soon realized, though, was that he had his own quite adequate methods of categorization, which had nothing to do with the way Scarry was dividing up the world. When the book had covered the first ten numbers, we came upon a review page:

I read, "One Willy. Two bunnies."

Mason shouted, "Two Willies!"

I read, "Three bunnies and three trucks."

Mason shreeked, "Three Willies!"

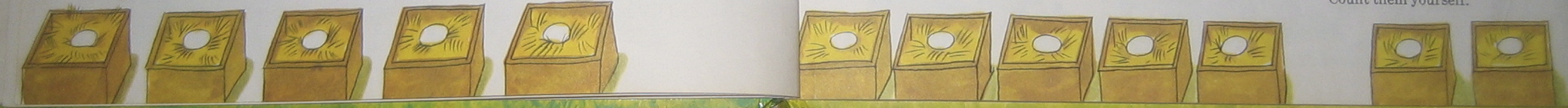

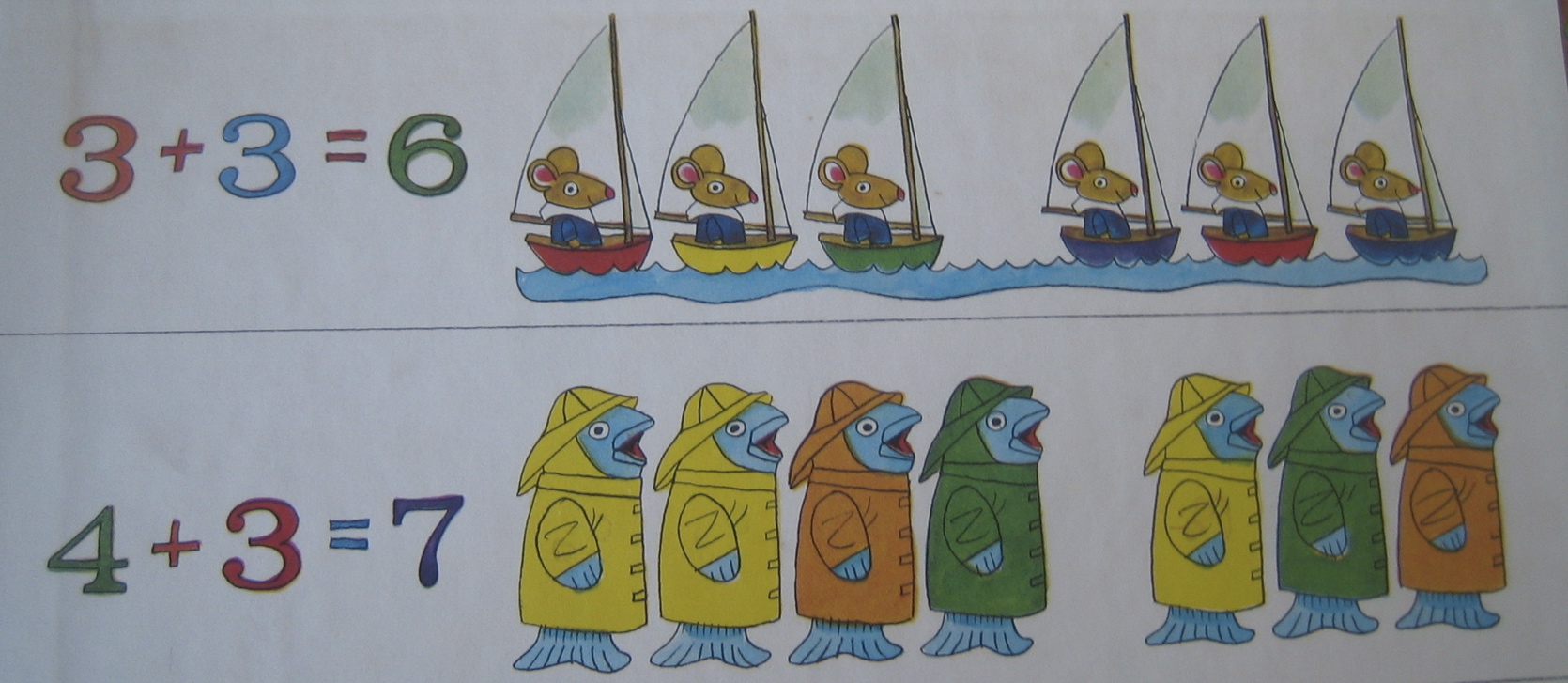

When Scarry turned to the larger numbers, his images always broke them down into groups: "Farmer Cat goes into the chicken house to gather eggs...five hens are red. Five of them are white. And two more are black. Twelve hens in all--they laid twelve eggs...count them yourself."

Mason hollared, "One egg is missing!!"

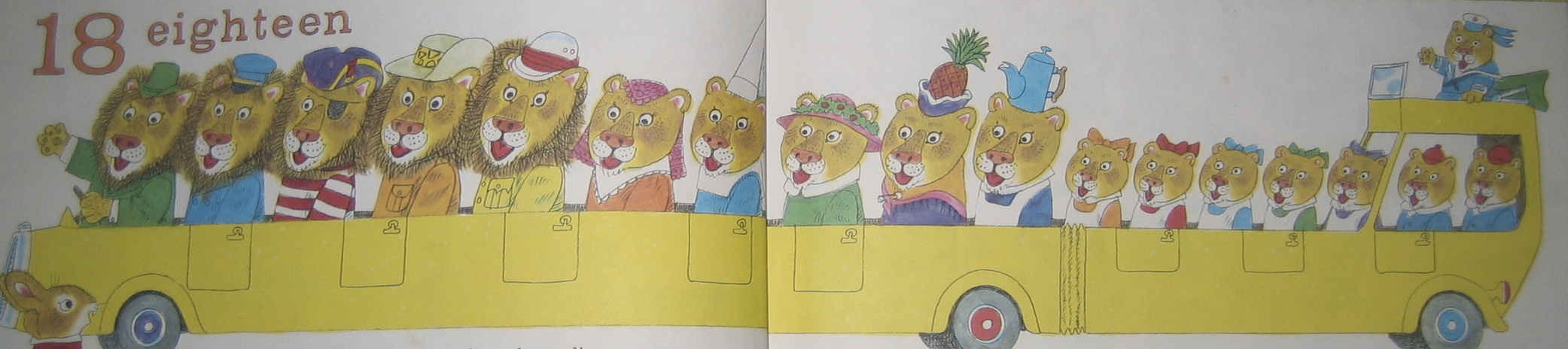

When, a few pages later, a long car drove by "with eighteen happy lions," Mason pointed out again, with some agitation, "there' s a lion missing!"--and then, with relieved delight, "There's the missing lion! He's the little guy, sitting up on top!"

When we reached the final page, where addition is introduced, Mason noted that two of the pigs were eating chocolate ice cream (which he'd had earlier that day); I pointed out that two of them had raspberry (which I'd had, too). He then said that one of the pigs had an "orange" cone. I said, "No, that ice cream is yellow. It must be lemon." He turned quickly to the next page, and shouted, "Lemon slickers! And there's a lemon boat!"

So: how would you assess what this child learned? How much learning needs to identify, ahead of time, what the goals are? How possible might it be to give a child an experience, and measure what he has learned from it, without measuring it against a pre-determined rubric of what is "right" and "wrong"?

Comments

Post new comment