Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Models of Mental Health: A Critique and Prospectus

Models of Mental Health:

A Critique and Prospectus

Expanding the view:

the "biological/neurobiological/cultural model"

A novel element of the broader perspective is the presumption that humans are nothing more (and nothing less) than complex assemblies of matter. This presumption derives in part from the kinds of clinical observations and experiences that the "medical model" makes use of but derives as well from additional biological and neurobiological observations to make a broader claim that includes not only aspects of the body, as that term is often used, but also internal human experiences (ie, "mind"). Most importantly, the broader claim makes it possible to bring together in one integrated framework not only the body and the mind but the self and culture as well. We do not regard the "materialism" assumption as "true" but rather as one that reasonably summarizes available observations and seems to open productive new directions for thinking about mental health (among other things). We will consider it further in a concluding section but note for the moment that it in not equivalent to denying the admissibility or significance of terms like "choice" or "self-determination" or "spiritual experience". As Emily Dickinson said "The Brain in Wider than the Sky ..." and so there is plenty of room within the brain for all aspects of human experiences.

A traditional view of body/mind/culture

The biological/neurobiological/cultural perspective

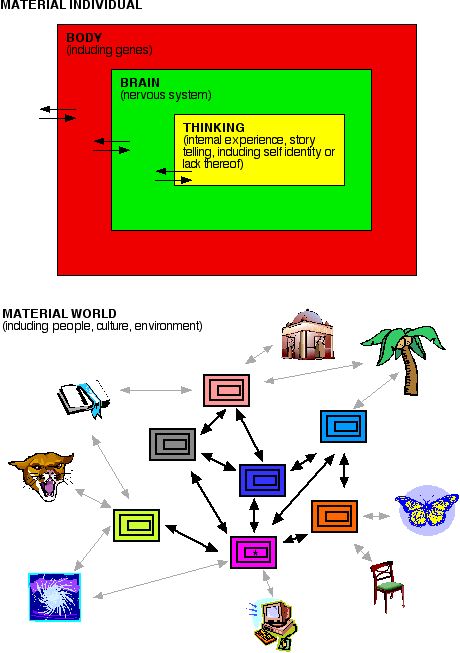

As shown in the upper part of the figure, an individual consists of a body that contains within it a brain which in turn contains a sub-region of the brain that supports internal experiences. The "self", as discussed in the previous section, is an emergent product of the body interacting with both the unconscious (green) and the conscious (yellow) parts of the brain, with the "experienced self" restricted to the latter. Since conscious thinking is dependent on prior processes occurring in the body and the unconscious parts of the brain, it is not only the "self" but all understandings of the outside world that have a "subjective" element to them. This is a significant challenge to any absolute standard of "objectivity" but also provides the opening by which change can occur in understandings both of oneself and the world. This scheme is not only consistent with all existing biological and neurobiological observations but provides a clear way to visualize the complexity of the self as well as of the various influences on it. Moreover, since each of the nested boxes is both influenced by and influences its surrounding box, there is a clear mechanism by which the experienced self can play a role in its own construction and revision. The scheme also appropriately (we think) emphasizes that neither "brain" and "body" nor "body" and "mind" nor "brain" and "mind" are separate and distinct entities (as sometimes thought). Mind is an aspect of the brain which is in turn an aspect of the body. Hence what affects the body can affect the mind, and vice versa. The lower part of the figure extends the nested notion to incorporate as well both individual experiences and culture. Individuals interact with an outside world that consists of both inanimate and animate entities. Among these are both other individuals and the collective products of individuals working together such as libraries and the like. The interactions among individuals and the products of such interactions are what we call culture. Several aspects of this further nesting are particularly important in the context of thinking about perspectives on mental health. One is the recognition that culture does not exist independently of individual human beings. It is instead the product of the interaction of human beings, and so individuals are both influenced by and capable of influencing culture. The second important point is that cultures emerge from diverse groups of individuals, each of whom is simultaneously engaged in a process of shaping and reshaping their own lives as well as participating in such a continual shaping and reshaping of community lives.

Conclusions

The usefulness of a broader perspective relates not only to its ability to provide a common framework in which insights from diverse perspectives can be brought together but also to its ability to generate from that diversity new issues that deserve more general attention. In the following section, we discuss some of the likely growing points that could emerge from the "biological/neurobiological/cultural" model of mental health, including the important questions of the potentials and limits of individual change and their relation to cultural change. |

This synthesis of a variety of materials on Serendip grew out of discussion in the Serendip/SciSoc Group Summer 2006 and was prepared by Paul Grobstein and Laura Cyckowski. Your comments and further thoughts are warmly welcomed by using the form below or by contacting us.

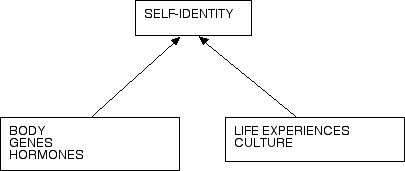

As schematized to the right, many people today think of themselves as the product of two separate and distinct kinds of influences: nature or "biology" (their bodies, influenced by genes, hormones, and so forth) and "nurture", a distinct sphere of experiential and cultural influences. Such a scheme embodies a useful distinction between things going on inside one and things influencing one from outside. It also is a comfortable fit to the "medical" model in that it distinguishes "biology" (around which the medical model develop) from other things. Notice thought that it gives no clear place for "brain" and portrays the "self" as the passive resultant of forces on which it itself has no influence.

As schematized to the right, many people today think of themselves as the product of two separate and distinct kinds of influences: nature or "biology" (their bodies, influenced by genes, hormones, and so forth) and "nurture", a distinct sphere of experiential and cultural influences. Such a scheme embodies a useful distinction between things going on inside one and things influencing one from outside. It also is a comfortable fit to the "medical" model in that it distinguishes "biology" (around which the medical model develop) from other things. Notice thought that it gives no clear place for "brain" and portrays the "self" as the passive resultant of forces on which it itself has no influence.

Comments

Social Model of Health

how does the social model of health help and hinder treatment for the mentally ill?

Post new comment